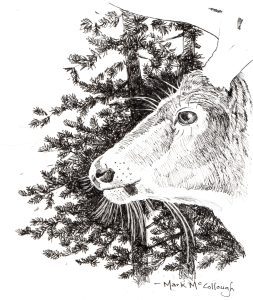

The Whisker Thing

By Mark McCollough

You do not see many blind deer…or foxes, or flying squirrels for that matter. How do they run at breakneck speeds (or glide in the case of flying squirrels) headlong through the dense forest without eventually ‘poking their eyes out?’ How do they travel swift-of-foot through a winter forest as dark as coals from last night’s campfire without crashing into things? The answer is a super-sense. One that you and I cannot even fathom…whiskers.

Nearly all mammals are endowed with facial whiskers or vibrissae as they are known to biologists. We see these thick, tactile hairs growing from the nose, cheeks, chins, and eyebrows of our dogs and cats, but rarely pause to ponder what they are used for. No wonder that humans are in the dark about whiskers, we lost our vibrissae along the evolutionary path about 800,000 years ago. We and platypuses are the only mammals that do not have vibrissae, but all the other mammals depend on them for many important functions. Science is just beginning to unravel the secrets of this amazing sensory system.

Whiskers are slender rod-like structures made from keratin. They are more similar to your fingernail than hair. They join the body in a large follicle surrounded by a dense network of nerves. If you have ever found a whisker on the floor from your dog or cat, you know that it is curved and tapered – thick at the base and fine and flexible toward the tip. As you might expect, this allows better sensing, especially when distinguishing textures of the objects that a deer or cat brushes up against.

Special Whiskers

Most prominent on mammals are “mustacial” whiskers under the nose that are arranged in a grid of ordered rows and columns. Early naturalists categorized the rows and columns between different mammal species. That was the most that we knew about whiskers for about a hundred years.

We now know that mammals with the most prominent whiskers are nocturnal and arboreal (e.g., flying squirrels, shrews, mice), aquatic mammals (e.g., otters, beavers), and marine mammals (walruses, seals). Daytime mammals such as horses, deer, and apes tend to have fewer and less-organized whiskers. Whiskers act as a 6th sense, operating closely with vision, smell, and hearing. Mammals can position their whiskers forward or back to heighten their sensitivity or to better explore what is in front of them.

Whiskers bend when they contact a surface. That bending is sensed by nerve receptors within the follicles that is telegraphed to the brain. In fact, a mammal seems to have a map of the grid of whiskers to analyze structures they encounter in complete darkness. Whiskers are also able to sense water and air currents. Walruses and seals have 10 times more nerve endings at the base of their whiskers than your dog. This implies that whiskers are essential to the survival of these animals in the dark waters they inhabit.

Bobcats and cougars (and your housecat) have sensor whiskers on their forelegs. It is thought these whiskers help them navigate in the dark, but also to help them climb and to better sense and grip their struggling prey.

Some mammals twitch their whiskers to heighten their sensitivity. Squirrels and mice can rapidly move their whiskers with special facial muscles in a behavior called “whisking.” This causes the tip of the whiskers or vibrissae to vibrate rapidly back and forth – so fast that it cannot be detected by humans. Whisking is only evident in nocturnal and tree-inhabiting species and enables them to quickly scan their environment.

Why Whiskers?

Why do most mammals have whiskers? The long, organized whiskers of mice, otters, and foxes undoubtedly help them orient and move through a dark environment. The ever-twitching whiskers of a shrew leads them through crevices and small spaces in their never-ending search for food. The thick vibrissae of otters and seals are able to sense the wakes of fish as they swim through the water. Deer, carnivores, and other mammals probably use their whiskers to detect minute changes in wind speed and direction. This, combined with superb sense of smell, allows deer to detect a stealthy hunter creeping through the woods. Bats and whales depend more on echolocation to find their prey and so have diminished whiskers. Dolphins are born with whiskers that are lost as they mature. The whisker follicles are retained and used as specialized electro-sensing organs to detect fish instead. Whiskers also play a role in social interactions. Think of a doe and fawn meeting in a meadow and touching noses and whiskers to greet each other.

Whiskers even have a practical use in wildlife conservation. Whisker patterns on a mammal’s muzzle differ from one individual to another. This has been used in studies to identify individual lions, sea lions and polar bears. Artificial intelligence software is being used to map whisker positions from photographs and help wildlife biologists to identify individual mammals.

It’s difficult for us to imagine the sensations that other mammals derive from their whiskers. I suppose the best we can conjure is a network of sensors protruding inches from various parts of our face, constantly feeling the breeze, detecting objects we encounter in the dark, and perhaps enhancing our senses of smell, vision, and taste. Too bad we lost this super-sense eons ago. But whiskers do explain why deer can run through the woods without ‘poking their eyes out.’

For more articles about hunting, fishing and the great outdoors be sure to subscribe to the Northwoods Sporting Journal.